A given person likes (loves) you as much as you like (love) him or her.Hmm. This is a thesis in search of a foundation. Tyler has some guesses about the mechanism(s) behind symmetry, but he seems more certain of the equilibrium than the process that leads to it.

...Let me rule out or explain some obvious “counterexamples.” If a guy stalks you, and you can't stand him, the reality is that he is probably more hostile to you than loving. The thesis fits.

Break-ups are tricky and they provide the best counterexamples. But who really left whom is not always obvious; it can take several years to figure out what was going on. Often the leaving party is the one who first develops a narrative of how things might be different; this is distinct from liking or loving the other person less. Other people leave pre-emptively.

Unilateral crushes are possible and indeed common, although with repeated contact they usually collapse into symmetry, one way or the other.

I’ll resist the temptation to jump into the old neoclassical-versus-Austrian debate about the relative importance of equilibrium and process analysis. Instead, I’ll offer my own attempt at a model of the phenomenon involved. This is just one of about four models I cooked up while proctoring an exam. It’s one that both supports Tyler’s thesis (some plausible models didn’t) and replicates the salient features of many relationships I’ve observed.

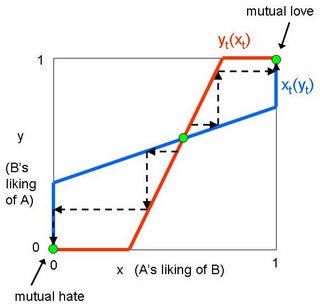

Assumptions: Let xt designate person A’s liking of person B at time t, and yt person B’s liking of person A at time t. Liking ranges from 0 to 1, with 0 = hate and 1 = love. Each person’s liking is a positive function of the other’s liking; that is, the more someone likes you, the more you’re inclined to like them. (Why? I think it’s because we are flattered. Also, if someone likes you, it’s a sign of their good taste!) I’m also omitting a couple of additional assumptions necessary to justify the functional forms in the diagram below.

The green spots in the diagram are equilibrium points. There are two stable equilibria in this situation: (1, 1), meaning that both people love each other, and (0, 0), meaning both hate each other. The middle point is also an equilibrium, but it is unstable. If either person’s liking of the other changes the slightest bit, it sets in motion a chain reaction that will lead to one of the two stable equilibria. Why? That’s where the process analysis comes in. If one person A starts to like B a little more, it initiates a virtuous process: B responds by liking A more, causing A to like B a little more, causing B to like A a little more, until true love is achieved. On the other hand, if A starts to like B a little less, it triggers a vicious process: B responds by liking A less, causing A to like B a little less, causing B to like A a little less, until they arrive in a state of mutual hatred.

The green spots in the diagram are equilibrium points. There are two stable equilibria in this situation: (1, 1), meaning that both people love each other, and (0, 0), meaning both hate each other. The middle point is also an equilibrium, but it is unstable. If either person’s liking of the other changes the slightest bit, it sets in motion a chain reaction that will lead to one of the two stable equilibria. Why? That’s where the process analysis comes in. If one person A starts to like B a little more, it initiates a virtuous process: B responds by liking A more, causing A to like B a little more, causing B to like A a little more, until true love is achieved. On the other hand, if A starts to like B a little less, it triggers a vicious process: B responds by liking A less, causing A to like B a little less, causing B to like A a little less, until they arrive in a state of mutual hatred.It might appear that all three equilibria fit with Tyler’s symmetry thesis. But slight changes in the functional forms (longer or shorter flat pieces, slight curvature in the functions) could result in the middle equilibrium lying off the 45-degree line. Nevertheless, Tyler’s thesis is vindicated by that equilibrium’s instability. We don’t expect the relationship to remain in that state for long, and eventually the parties will fall into mutual love or hate.

There is no middle ground

Or that’s how it seems

For us to walk or to take

Instead we tumble down

Either side, left or right

To love, or to hate.

- Peter Murphy, A Strange Kind of Love

2 comments:

hmmmm. does this analysis leave room for that phenomenon, "the ickies"? that is, say a couple starts out liking one another equally. after a while, the more the mate seems to like you, the less you like him because he's moving too fast and now looks needy and desperate. this gives you the ickies. things fall apart. but he swears he will always love you.

(and no, this is not a veiled reference to your co-blogger. he does not give me the ickies.)

Nope, it doesn't cover that case. I do have a little model for that case, but I decided to post this one because it was more fun and supported Tyler's thesis. What's interesting is that if *both* parties have the kind of liking-functions necessary for the ickies, then (I think) you get multiple equilibria just like the presented model, except that both stable points are love-hate relationships (one person crazy in love, the other person hating and freaking out).

Post a Comment