Condoms, cheap pizza, beer, lotto tickets, bongs, military gear . . . what have they got to do with the rule of law? LearnLiberty, a project sponsored by the the Institute for Humane Studies, recently aired a video that I wrote and narrated on the question. Enjoy!

Friday, February 18, 2011

Condoms, Cheap Pizza, Beer, and . . . the Rule of Law

Wednesday, June 02, 2010

A T-Shirt to Save Miranda

Professor Crim Pro I ain't, but it seems to me that anybody who has used a computer can pretty easily grasp the holding of Berghuis v. Thompkins, 560 U.S. __, No. 08-1470 (June 1, 2010) [PDF]. In that opinion, handed down just yesterday, the U.S. Supreme Court toggled the default on the Miranda warning. A five-justice majority held that silence will not suffice for citizens who want to invoke Miranda's protections against self-incrimination; we now must ask for our Constitutional rights. Think of it like a computer program that annoyingly assumes you want unsolicited advice from a chirpy paper clip--except this paper clip throws you in cuffs and tazes you if you talk back.

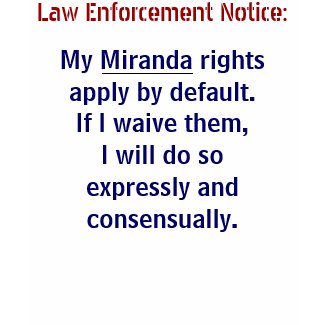

The Berghuis decision inspires me to offer a new piece of legal armor—this time in the form of a t-shirt:

Click on the picture to buy a shirt, or borrow the text (I've uncopyrighted it) to make your own version from scratch. Combine that notice of your Miranda rights with the bumper sticker and magnetic sign I offered earlier, in defense of your rights to record and report what public officials do to you, and you might just dodge some serious legal hurt. Or—who knows?—you might inspire some interesting and important litigation.

I leave detailed analysis of how Berghuis jibes with Miranda and other precedents to other, more knowledgeable commentators (see supra, "ain't Prof. Crim Pro" disclaimer). I dare say, though, that Justice Sotomayor's dissent hit a nice note:

Today’s decision turns Miranda upside down. Criminal suspects must now unambiguously invoke their right to remain silent—which, counterintuitively, requires them to speak. At the same time, suspects will be legally presumed to have waived their rights even if they have given no clear expression of their intent to do so. Those results, in my view, find no basis in Miranda or our subsequent cases and are inconsistent with the fair-trial principles on which those precedents are grounded.Slip. op. at 23 (Sotomayor, J. dissenting).

I guess that you could say the Berghuis majority took a cue from the (so-called) libertarian paternalists and engaged in some legal nudging. In this case, however, the Court nudged our defaults away from individual liberty and toward prosecutorial power. Call it statist paternalism.

Thanks, Supremes, for giving us worse than nothing. Ah, well. As I read Berghuis, even the justices in the majority would not deny us the opportunity to answer their new default with a firm "No!" Thus might we recover our Constitutional rights with a t-shirt.

[Crossposted at Agoraphilia and The Technology Liberation Front.]

Monday, December 01, 2008

Hello, Jonah

Like it or not, we live in the belly of Leviathan. Friends of liberty tend not to like it. Rather than giving in to death-by-digestion, or the dreaded Lower Intestines of Statism, they struggle to escape. Hello, Jonah, describes that plight, prescribes a cure, and wryly notes the outcome:

As with Nice to Be Wanted, Sensible Khakis and Take Up the Flame, a Creative Commons license allows pretty free non-commercial use of Hello, Jonah. You can find the words and chords here.

As for (admittedly unlikely) commercial licensees, Hello, Jonah asks that they tithe 10% of revenues to the Cato Institute. I worked at Cato some years ago, and continue to support its good works. Like Jonah, Geppetto, and Pinnochio, Cato works from within the belly of the Beast, helping us all of us who "struggle to get out."

[Crossposted at Agoraphilia and Technology Liberation Front.]

Saturday, November 08, 2008

"Take Up the Flame"

The fight for freedom has seen brighter days, I grant. I think it will see still brighter days yet, though, if we can encourage another generation to join the cause. Towards that end, I wrote a song, "Take Up the Flame":

As the song's credits indicate, I've dedicated the song to my old friend and mentor, Walter E. Grinder—one of the many people who inspired me to take up "the flame." I originally planned to debut the song at a conference planned by the West Coast chapter of the Students for Liberty, to be held at Stanford University in mid-November. I figured that Walter, who lives nearby, could hear the tune in person. That meeting got cancelled, alas. Not to be deterred, though, I'm now distributing the song virtually.

The song's credits also indicate that I've released it under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 3.0 Unported License, and made the lyrics and chords freely available for downloading. It would delight me if somewhere, someday, "Take Up the Flame" helped to raise the spirits of young folks rallying for the Good Fight. (Although I don't imagine anyone will find much reason to license the song commercially, I've also stipulated that any such licensee must agree to tithe a portion of the proceeds—10% of income, traditionally—to the Institute for Humane Studies, an organization that has long taught students about liberty.) Sing it loudly and proudly, friends of freedom!

[Crossposted at Agoraphilia and Technology Liberation Front.]

Wednesday, June 04, 2008

Upgrading the Pledge of Allegiance

Back in 2005, I criticized the U.S. Pledge of Allegiance and offered an improved alternative. My version of aimed to correct "the odiously unconditional" demands of the present pledge and thus better honor the ideals that gave rise to the U.S. in the first place. Field testing and theoretical musing convinced me, however, that I needed to have another go at debugging the Pledge of Allegiance. I here offer an upgrade for 2008:

I pledge allegiance to the laws of the United States of America, on condition that it respect my rights, natural, constitutional, and statuory, with liberty and justice for all.

Why upgrade to Pledge v. 2008? For one thing, it matches the cadences of the currently popular pledge—which history suggests we might call "v. 1954"—more closely than my earlier alternative did. It proves especially helpful, when you're saying this latest version in a crowd, that it starts and ends with the same words that everybody else says. It also follows the same cadences as v. 1954; consider the following parallels:

| Pledge v. 1954 | Pledge v. 2008 |

| I pledge allegiance | I pledge allegiance |

| to the flag | to the laws |

| of the United States of America, | of the United States of America, |

| and to the Republic | on condition that |

| for which it stands, | it respect my rights, |

| one Nation | natural, |

| under God, | constitutional, |

| indivisible, | and statutory, |

| with liberty and justice for all. | with liberty and justice for all. |

I also tweaked the content of this latest version of the pledge to make it still more palatable to friends of liberty. Note, for instance, that it now has you pledge allegiance not to the flag, nor even to the political institution for which that flag stands, but rather to "the laws of the United States of America." After all, a republic that breaks its own laws does not deserve your allegiance.

Note, too, that v. 2008 conditions your allegiance on the U.S. respecting three kinds of rights you can claim—natural, constitutional, and statutory. This upgraded pledge thus offers powerful protections for your liberty. Indeed, you might well wonder whether, given those strict conditions, Pledge v. 2008 commits you to anything at all! I leave the answer to that question, however, to the dictates of your conscience.

Saturday, April 19, 2008

Amsterdam on the Reservation

I'm currently attending a Liberty Fund conference on, "Liberty, Property, and Native America." The assigned readings, drawn largely from Self-Determination: The Other Path for Native Americans (2008), have exposed me to a wonderful range of new ideas. The chapter written by Ronald N. Johnson, for instance, "Indian Casinos: Another Tragedy of the Commons," opened my eyes to a way by which Native Americans might both radically increase their fortunes and our liberties. The idea, in brief: The same loophole that allows them to run casinos might also allow Indians to offer legal access to recreational drugs, prostitution, and extreme fighting.

Native Americans won the right to run casinos thanks to cases like California v. Cabazon Band of Indians, 480 U.S. 202 (1987), and Seminole Tribe of Florida v. Butterworth, 658 F.2d 310 (5th Cir. 1981), and the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act ("IGRA") that such cases inspired. To generalize, U.S. law allows sovereign tribes to offer gaming services on their reservations, subject to three conditions:

- First and foremost, a reservation's host state must permit the particular sort of activities in question, even if under a very restrictive regulatory regime, rather than prohibiting and criminalizing them. In Seminole Tribe of Florida, for instance, the tribe successfully relied on the claim that Florida law allowed certain forms of bingo.

- Second, to judge from cases forbidding the sale of fireworks on reservations, and the illegality of Indians offering Internet gaming to off-reservation customers, a tribe must not exercise its sovereign powers so as to gut the effect of its host state's regulations. What happens on the reservation must, in other words, stay there.

- Third, as a matter of rhetoric if not hard law, it helps a tribe to emphasize that it has a long history of enjoying the same amusements that it offers its guests. Indian casinos thus often emphasize the role that games of chance traditionally played in the host tribe's culture.

Depending on the state and tribe, those three conditions might apply to a tribe offering recreational drugs, prostitution, and extreme fighting on its reservation. Thanks to Employment Division v. Smith, 494 U.S. 872 (1990), and 42 U.S.C. 1996a, for instance, states must permit the religious use of peyote, a traditional practice among some Native Americans. So long as a tribe administers that sacrament under controlled conditions, rather than by selling it for off-reservation use off, offering peyote would arguably qualify for the same sort of legal protections that have allow Indian casinos to thrive. Similar arguments might well apply to marijuana in many states (though here the case for traditional Indian use appears weaker than with regard to peyote), prostitution in Nevada and Rhode Island (though, again, the alleged "wife sharing" customs of some tribes do not quite equate to the same practice), and violent or even deadly sports among consenting adults.

According to Ambrose L. Lane, Sr.'s book, Return of the Buffalo: The Story Behind America's Indian Gaming Explosion 44 (1995), in 1979, California's Cabazon Band of Mission Indians considered cultivating marijuana and jimson week (a traditional Native American hallucinagen), only to set the idea aside. Beyond that, I've found no evidence that any tribe has considered pursuing the sort of legal strategy I've described. Given the large profits that offering drugs, sex, or extreme martial arts might garner tribes, however, and the competition that increasingly cuts into their gambling businesses, we might soon see many Native American Amsterdams.

Friday, April 04, 2008

Obama: An Oppressed Minority Who Might End the War

As an oppressed minority, Barak Obama has seen life from a perspective all too rare among politicians. He has suffered being cast out of restaurants and other public accomodations. He has strived to pass himself off as a member of the ruling majority, only to have his efforts cast into doubt and his minority status thrown back into his face. Some people think that none of this matters—that we should not discuss Obama's minority status, much less consider it as a factor in his candidacy. To the contrary, I think we should celebrate it as a something that makes him more likely than McCain or Clinton to pursue a policy of peace.

I refer, of course, to Obama's nicotene habit and how it might encourage him to take a fresh perspective on the ongoing Drug War.

As a cigarette smoker, Obama has, like others in that oppressed minority, suffered shame and rejection. Obama has evidently tried to stop or at least hide his habit, only to have reporters badger him about his efforts and doubt his sincerity. Some people think we shouldn't care whether or not Obama smokes. As someone who struggles with addiction daily, though, Obama surely knows better than most that criminalizing drugs offers a very poor way to help the afflicted. More than any other presidential candidate, he can understand first-hand the appeal of recreational drugs, and can empathize with those who let their bad habits get the best of them.

Thanks to his addiction to cigarettes, Obama offers us the hope of a kinder, freer, more peaceful America.

Tuesday, January 15, 2008

A Casting Out of Thousands

Well, see, here’s the danger in even suggesting ideological excommunication. From the comments on my prior post:

But while we're excommunicating people from the libertarian movement, why not include Palmer and his associates at CATO? After all, many of them endorsed the concept of preemptive war, which last time I checked violates oh, the entire philosophical underpinning of libertarianism. And it is CATO that is chiefly responsible for the view that libertarians are mere apologists for Big Business. ... By all means, lets cleanup the libertarian tent -- but lets make sure we're thorough when we do it.Look, if we start kicking people out every time we disagree with them on one issue or another, pretty soon it’ll be an empty tent. There are very few issues I would consider libertarian litmus tests, and almost none of them fall in the difficult realm of foreign policy. Yes, I think libertarians who supported the war made a big mistake. But there’s an awful lot of Monday-morning quarterbacking on this issue. I’m pleased with myself for having opposed the war in Iraq before it started, on grounds that it would lead to a quagmire and incite terrorism. But at the time, I confess that I considered it something of a close call, especially since I thought it likely Iraq actually did have WMDs (yes, I too was fooled).

I wouldn’t even categorically rule out preemptive attacks, although I think they’re generally a bad idea, as Iraq so aptly demonstrates. When I was in middle school and the target of multiple bullies, I remember a lesson my dad taught me: “Avoid a fight if you can,” he said, “but once you know it’s coming, it’s better to hit first than to go down before you get the chance to hit back.” To delve into libertarian theory just a tiny bit, libertarians say it’s wrong to initiate force or the threat of force against another. But threats aren’t always explicit and verbal, and some judgment is required to identify them.

Point being, there are plenty of debatable points within libertarianism. I’ve argued far more with libertarians than with any other ideological group, despite being a libertarian myself. If every one of these debates led to schism, there would be no libertarian movement left. And the problem gets even worse if excommunications are based on association with a particular organization, simply because someone there has taken a disagreeable position. Take Cato, for instance; the commenter quoted above says that “many” people there supported the Iraq war. It’s true, some Cato staff did support the war. But their actual foreign policy experts did not! Those who supported the war did so on their personal blogs and in other publications, and they spoke only for themselves. To excommunicate everyone at Cato based on the position taken by a few individuals would result in a pretty substantial error of over-inclusion.

So why have I taken a different stance with respect to the Mises Institute? First, I have been careful to distinguish between the Institute generally and the specific individuals responsible for the racist material in question. If the Institute deserves blame of a general nature, it is only because its founder and president is one of the more execrable people involved.

Second, I’m not actually proposing a policy-based litmus test. I’m not saying we should denounce these people for their position on, say, immigration (though I do strongly disagree with them on that issue). I’m saying we should denounce them for their racism, regardless of what policies it leads them to endorse. Even if their racism leads them to policy conclusions we find attractive on other grounds (like rolling back the welfare state), the racism itself is a problem. Why? Because racism is poison. Even just tolerating racists is a damn good way to make sure most decent people will never listen to you again.

Third, as commenter Gil says, “I've never felt aligned with Rockwell, but I can’t keep him from calling himself a libertarian. There isn't an official libertarian seal of approval, and I don't think there should be.” So we’re not talking about actual censorship here. We can’t stop these people from blogging, writing newsletters, publishing papers, and calling themselves whatever they want. What we can do is refuse to associate with them, refuse to publish with them, refuse to acknowledge them as part of our community. Not because they have the wrong policy prescriptions – sometimes they are right – but because we find them unsavory, and because by allowing ourselves to be associated with them we run the risk of tainting our own views.

Friday, January 11, 2008

Whom to Cast Out and Why

Tim Sandefur says the time has come for libertarians as a group to excommunicate the racist-paleoconservatives among us – especially those associated with Lew Rockwell and the (criminally misnamed) Mises Institute.

[W]e need to face up to the serious conflict within our ranks, between the neo-Confederates at the Mises Institute on one hand, and what James Kirchik calls “the urbane libertarians who staff the Cato Institute or the libertines at Reason magazine” on the other. … I would like to see the libertarian community as a body repudiate the Lew Rockwellers entirely. They are not libertarians, they are paleo-conservatives who do not share our primary concern with individual liberty and constitutionalism. Ultimately they lack a grounded perspective on what liberty means and why it is important. Their moral and cultural relativism, their traditionalism and their alliances (both intellectual and strategic) with southern-style paleo-cons have misled them in many ways.I am inclined to agree. While I generally favor a big-tent approach to libertarianism, and I think internecine squabbles have damaged the movement, there are some alliances just not worth making. Tolerating racists only poisons the cause.

We should recognize, however, that not everyone associated with the Mises Institute is a horrible person, just a number of bad seeds like Rockwell and Hans-Hermann Hoppe who unfortunately wield a great deal of influence. So we should be careful in how we word our denunciations.

Sandefur also delves into why we haven’t removed this tumor already, and here I think he goes astray. He essentially lays the blame at the feet of the consequentialist/utilitarian strain of libertarian thought:

Pragmatism—that is, the consequentialism of which Mises is the most obvious spokesman—was designed exactly to avoid these questions, because they lead to such conflict. We’ll just create a wertfrei [value-free] libertarianism, Mises thought, and then we can avoid all this morality stuff and just get to designing a free society. The upside? You can convert people of different moral backgrounds to libertarianism. The downside? It collapses at the touch of those who take relativism seriously, and [who] reject the practical arguments for liberty because they’re concerned more with their allegedly moral vision of a totalitarian state. … And then there’s the orneriness—the libertarians who think they’re special because they reject all those old-fashioned moralizers like Rand and Jefferson and whatnot. They’re much too sophisticated and mature, you know, for discussions over morality and objectivity and deontology and whatnot, and if you suggest that there’s something wrong with a libertarianism that is not grounded in ethics, you’re just, like, totally lame.This is almost exactly backward. I’m pretty sure that if you did a quick poll, you’d discover that Cato and Reason are where you’ll find the most consequentialist and pragmatic libertarians, and the Mises Institute is where you’ll find the most deontologists. It’s the Rockwell-types who constantly claim their positions are objectively true and follow directly from a prior reasoning. Now, I’m not claiming there’s a causal connection between deontology and racism/paleoconservatism; it’s only a correlation. But the correlation runs exactly opposite to that posited by Sandefur.

The Mises name is a source of confusion here, because Ludwig von Mises stood on both sides of the divide. On the one hand, he was an a priori economic theorist. But he was also an adamant utilitarian consequentialist, something the Mises Institute folks prefer to ignore. More importantly, Mises was at his core a cosmopolitan, not a nativist. Mises’s views were in this respect diametrically opposed to those held by certain unsavory inhabitants of the Institute that bears his name.

Wednesday, January 09, 2008

The Libertarian Small Sample Problem

The Ron Paul newsletter scandal (summarized by Arnold Kling here and Radley Balko here) underscores what I see as the most difficult PR issue for libertarianism: the small-sample problem.

Given the relative rarity of libertarians, both in the public eye and in general, most people’s judgment of libertarianism will be based on a very small sample – often a sample size of one. If the first libertarian someone meets is a smart, reasonable, decent person, they will come away with a positive impression and possibly a willingness to explore further. If the first libertarian someone meets is a wild-eyed lunatic, on the other hand, they could easily write off libertarianism as the ideology of wild-eyed lunatics.

The Paul candidacy presents a special case of the small-sample problem. For many people, Ron Paul is the first and only libertarian-identified candidate they’ve ever seen receive any serious media attention. As a result, they may assume other libertarians share all of his views. Many libertarians, including Kling, are wary of supporting Paul – even though they probably agree more with Paul than anyone else in the field – because they fear the public will assume that all libertarians are anti-immigrant gold-bug conspiracy theorists (and possible closet racists).

Liberals and conservatives don’t have this problem. Everyone understands that these groups contain a gamut of opinion, with some degree of disagreement on every issue. If one candidate goes off the reservation on one issue or another, there’s no real fear that his position will define the movement forever.

This is why, when I talk to young libertarians about how to spread their ideas, I say they should think of themselves as ambassadors for the movement. That means, first and foremost, presenting themselves as fundamentally decent people that you would actually want to have a beer with; and second, being willing to admit the diversity of libertarian thought (“libertarians don’t all agree on this, but…”) before pushing their own peculiar views.

As an aside, I think one reason libertarian ideas have fared so well in the blogging world is that there are enough libertarians online, of both the reasonable and kooky varieties, that non-libertarian political bloggers usually have a fair sense of what libertarians think in general (notwithstanding the occasional smear).

Tuesday, August 14, 2007

Anarchy Rebound

At Cato Unbound, Peter Leeson has reignited the intra-libertarian debate on minarchism versus anarchism. Bruce Benson, Dani Rodrik, and Randall Holcombe all have responses up.

When I argue with libertarian anarchists, it’s often like an out-of-body experience: I suddenly feel like I know how others see me. I regard libertarian anarchists in much the same way that non-libertarians must regard libertarians in general: kinda wacky, often very smart and well-read, idealistic, lacking in political realism, and a little too confident in the power of their own ideas. It gives me a dose of humility about my own perspective.

That’s not intended as a serious criticism of anarchism, or of any particular anarchist (since some are more reasonable than others). Just as I think non-libertarians ought to take libertarianism seriously, libertarians ought to take anarchism seriously, at least as a test of the limits of our own ideas. The fact that a position is “extreme” is not an argument against it. But at the end of the day, I’ve just never bought it.

My primary objection to anarchism is that I don’t believe it’s sustainable – or as Holcombe puts it, it’s not a stable equilibrium. I’m unpersuaded by the examples of medieval Iceland and Ireland – first, because those were island societies relatively isolated from the outside world; and second, because those societies had much less anonymity than does modern society, allowing for social sanctions that would be much less effective now.

Moreover, these societies have to be put in the context of the rest of the history of civilization, in which states have emerged out of an initially anarchic context. I will sometimes ask anarchists, “What is it that makes the modern world not an example of a highly evolved anarchy?” States have not always existed, after all. As I see it, a stateless world is, by definition, anarchy – whether or not it has the desirable features that anarchists would like it to have. And out of that world, states arose, grew, and largely displaced other forms of organization. Even in Iceland and Ireland.

In response to this challenge, libertarian anarchists with whom I have argued usually say that the initial conditions for anarchy include more than the mere absence of states. There need to be a certain number of already-existing (and perhaps equal-sized) protection agencies, or power sources, or something like that. What this says to me is that anarchism is not an equilibrium that is likely to evolve or come into being spontaneously; those initial conditions have to arise through luck (Somalia) or deliberate choice (states voluntarily dissolving themselves?). This seems an odd position for people who place so much emphasis on the notion of spontaneous order to take.

So, in my estimation, libertarian anarchy is (a) unlikely to emerge in the first place, and (b) likely to evolve into states even if it somehow gets established to begin with. The best response I’ve heard from anarchists is that the minimal state has the same flaws. After all, there have been no truly minimal states in history, and those that have come close have all expanded into something much larger. Sadly, this is true. It is not, however, an argument for anarchism over minarchism; it’s an argument against both. Both varieties of libertarianism have an “ought implies can” problem. The anarchists seem to be saying, “Between two fantasy worlds A and B, I prefer A.” Where does that get us?

I think it gets us to Holcombe’s main argument, which is that anarchism is a dead letter in the policy debate. Maybe the minimal state is, too. But we can certainly try to move policy in a more libertarian direction. Part of that process is explaining to others how our ideas could possibly work in the real world. And here I must differ from Holcombe, who thinks anarchism is useful because it frames minimal-statism as a kind of middle ground: “[B]ecause anarchists extend the bounds of the political debate on the role of government, arguments to eliminate this tax or that regulation become more of a middle-of-the-road proposition.” Sometimes this kind of framing strategy works, but I don’t think this is one of those times. Instead, I think libertarianism of the kind that normal people might accept gets found guilty by association – “See, those libertarians really don’t think we should have government at all!”

If explaining how privatization of the police and military could work would help to advance libertarian ideas more generally, I could see its usefulness. But as sophisticated anarchists like David Friedman have recognized, they are not same ideas. The argument for the efficiency of a competitive market in (say) computers, set against the background of relatively well-enforced rights of property and contract, does not translate into an argument for the efficiency of a market whose function is the establishment and enforcement of those background rights. There’s a chicken-or-the-egg problem, and to overcome it the anarchists need different arguments. As a result, arguments for the viability of markets in rights protection – however convincing or unconvincing they may be – do little to move the debate forward in other areas.

Wednesday, May 09, 2007

Dan Klein on Coercion

Dan Klein has an excellent essay at Cato Unbound arguing (inter alia) that the distinction between coercion and voluntary agreement should occupy a central place in economic analysis:

Now, you might be muttering, “Yeah, whatever, but I’m interested in economics. I don’t care to ponder semantic issues about moral and political terminology. Let’s leave that to the philosophers.”The danger, as Klein acknowledges, is that focusing on coercion versus voluntarism might encourage more ideological – and thus less analytical – analysis. But the solution is to recognize forthrightly that “coercive” does not equal “always wrong.” It should be perfectly acceptable and comprehensible for an economist, even a libertarian one, to say of a particular policy that it is “coercive but still desirable on net.” For libertarian economists, such cases will be few; for other economists, they might be numerous. But at least we’d be on the same semantic page.

Hold on. We need the distinction between voluntary and coercive action to give meaning to “the free market.” We need it to identify an “intervention.” We need it to measure “economic freedom.” We use it to categorize classes of action, to identify and define industries, to formulate theoretical parallels between one industry and another, and between one polity and another. We use it to formulate reform proposals. Our theories about human interaction make key distinctions based on whether the interaction is voluntary. We generally assume that the individual is bettering his situation in voluntary interaction, but we don’t make the same assumptions in coerced interaction. The distinction between voluntary and coercive is built into many of the key analytic distinctions we use in economics. So it is important that we know what we mean by it.

I strongly agree with the overall point, but I think Klein exaggerates the sharpness of the concept of coercion. He defines coercion as “when someone brings physical aggression or threat thereof to your property,” and he defines property as “your stuff, including your person.” Klein admits to the existence of holes and gray areas, but still says “the basic ideas of tangible property, ownership, and consent are cogent and apply so widely that we may think of the exceptions as exceptions.”

Okay, maybe I’m just arguing over how large those holes and gray areas are. But the problem, as I see it, is that many disputes concern exactly what your property is to begin with. Let’s take what Klein regards as one of the few cases where coercion by private actors is routinely tolerated: “loud Harley-Davidsons.” Is this example so obvious? Yes, the Harleys impose noise pollution on nearby homes; this is a kind of negative externality. But as Ronald Coase observed, externalities are reciprocal in nature. To side with the motorcyclists is to harm the home owners – but to side with the homeowners is to harm the motorcyclists. The real question is, what does your home ownership really include? A right to absolute silence? Surely not. But then how many decibels is too much? Does it matter if the motorcyclists had been cycling in your area long before the homes were built? (Or for a more contentious example, does it matter if the airport was built before the nearby homes were constructed under its flight path?) The issue here is not one of coercion versus voluntarism, but of establishing initial property rights.

Klein may have intended the Harley example as a jest. But his more serious example of grazing rights in Montana, where the presumption is that others’ cattle may graze on your land unless you specifically fence them out, suffers from a similar problem. The question again is what rights you really possess in what is otherwise your land. Just as it’s not obvious that you have a right to absolute silence in your home, it’s not obvious you have an absolute right not to have others' animals wander across your yard. Even outside Montana, you don’t need permission in advance to possess animals that might escape and do damage to someone else’s assets – you merely have to pay for any damage after the fact. In other words, land is protected against trespass by animals with a liability rule rather than a property rule. Is Klein saying that all liability rules constitute a form of coercion? If so, that would mean almost the entirety of tort law is an exercise in coercion – which would seriously damage his claim that institutionalized coercion by private parties is “almost never tolerated.”

For these reasons, I would restrict the term “coercion” to two types of cases: (a) Where there is general agreement on initial property rights, and then some action (public or private) takes away those property rights and transfers them to someone else. (b) Where there is general agreement on initial property rights, and then some action (public or private) prevents the owners of those rights from voluntarily transferring them.

This more restrictive definition of coercion would not rob it of all meaning. Taxation clearly falls within category (a), since there is general agreement that your income (or whatever else is being taxed) is indeed yours to begin with, even if it “becomes” the government’s. The minimum wage – Klein’s starting point in this discussion – would clearly fall in category (b), since there is general agreement that workers own their labor and employers own their money and their businesses, yet the law prevents these parties from making voluntary exchanges at mutually agreeable prices. Most of the policies that Klein lists, from drug prohibition to FDA regulations to gun control, would fall into either (a) or (b) or both. And, as Klein indicates, recognizing these as forms of coercion does not necessarily mean opposing them.

Wednesday, March 14, 2007

Evolutionary Biology and the Libertarian Paradox

Tyler Cowen enunciates what he calls the “paradox of libertarianism”:

Libertarian ideas also have improved the quality of government. Few American politicians advocate central planning or an economy built around collective bargaining. Marxism has retreated in intellectual disgrace.There is something to this. Human beings seem to have some kind of built-in compassion gene that leads us to want to help others in times of abundance. There are good evolutionary reasons for that to be the case, a point that Paul Rubin emphasizes in his book Darwinian Politics (which figured prominently in a Liberty Fund event I attended recently). What is not so obvious is why this biological impulse should cash out in terms of policy – especially national policy. The human desire to help others was born of our origin in small groups and clans, most likely consisting of no more than a few hundred people at most. And notably, it’s in small-group contexts that charity is most effective, because it’s much easier in a small group to monitor the recipients for signs of shirking and moral hazard. It’s at least odd, then, that the compassionate impulse would manifest itself in modern society as a desire to help a “family” consisting of millions of people.

Those developments have brought us much greater wealth and much greater liberty, at least in the positive sense of greater life opportunities. They’ve also brought much bigger government. The more wealth we have, the more government we can afford. Furthermore, the better government operates, the more government people will demand. That is the fundamental paradox of libertarianism. Many initial victories bring later defeats.

I suspect that while the compassionate impulse is innate, its zone of application is malleable by culture. We have “nationalized” our compassion only because of historical factors that have aggrandized the nation-state over smaller political units, communities, churches, extended families, and so on. If I’m right, then it might be possible to redirect those impulses back toward the smaller groups where they are both less damaging and more effective.

Friday, July 09, 2004

Unfashionable Libertarians for Not-Bush

Virginia Postrel is one of the smartest libertarians around, but she’s got a big blind spot about the 2004 election. First, she makes the mistake of focusing on the presidential candidates’ platforms, instead of the dynamics of their interaction with Congress:

Vote for Kerry if you must, folks. But don't pretend you're doing it because Bush's economic policies are insufficiently free market or fiscally responsible. Kerry wouldn't be any better on economics. He'd be worse.I’ve said it before, and I’ll say it again: The pro-Kerry argument is not his platform. The pro-Kerry argument is gridlock. Tyler Cowen expands on the point.

Second, Virginia accuses Jacob Levy – and by implication, other libertarians – of supporting Kerry to be politically fashionable:

[first post] But all rationalizations aside, I have a sneaking suspicion that Kerry-leaning libertarian hawks (now that's a small demographic!) are simply kidding themselves in order to stay on the fashionable side of politics.This is at once bizarre and insulting. Libertarianism is a small, largely unknown ideology. Nobody’s a libertarian to be popular. Libertarians who “out” themselves often run a risk to their academic careers – a risk that is hardly mitigated by supporting one Democrat in one election. Bill Clinton was much more fashionable and popular than Bob Dole or the LP’s Harry Browne – so where were all the pro-Clinton libertarians in 1996? It is only now, in the light of the catastrophe that is the Bush administration, that libertarians have begun to express nostalgia for Clinton.

[second post] Jacob Levy claims geeky fashion sense and a messy office as a defense against my suggestion that his Kerry infatuation is a sign of trying to be cool. Sorry, Jacob (whom I like very much). Bad aesthetics is no excuse. Artists aren't the only ones who fashionably hate George W. So do academics.

No, when a libertarian vocally supports a Democrat, there’s clearly a reason. In this case, it’s because George W. Bush has been a miserable failure, by both libertarian and common-sense standards.

Now, there’s a legitimate question about whether libertarians should vote for Kerry or the LP’s Badnarik. On that question, I’m torn. But realistically, since Badnarik hasn’t the slightest chance of winning, we might as well ask who is the lesser of the two major-party evils. To me, the answer is clearly Kerry – not because of his platform, and not because I want to be popular, but because the GOP doesn’t discover its limited-government principles until there’s a Democrat in the White House.

So how do we put one there? Whether you vote for Kerry or Badnarik, you’re still subtracting votes from Bush – so far, so good. The argument for voting Kerry is that each vote is a two-vote swing (one less for Bush, one more for Kerry), while voting Badnarik is only a one-vote swing (one less for Bush, no more for Kerry). But libertarian votes cast for Kerry will be indistinguishable from the votes of all the anti-trade, anti-market, pro-tax, nanny-state left-wingers. On the other hand, votes for Badnarik – especially in a key state – can easily be interpreted as “people who might have supported Bush if he weren’t a total disaster.” I think that’s a message worth sending, which is why I’m leaning slightly toward Badnarik.

UPDATE: Virginia Postrel's initial accusation of popularity-seeking seems directed only at Kerry-leaning libertarian *hawks*, so maybe her point is that Bush is clearly better on the war & terrorism issues. Not being a hawk myself, I'm unsympathetic. In any case, her second post strongly indicates that she thinks Bush would be better on economic issues as well.

Friday, May 28, 2004

Block the Box

This op-ed by Chris Edwards contains a long list of proposals for new spending, all gleaned from the Kerry website. It really is appalling. Democrats who criticize the Bush Administration for its profligate spending have no business proposing laundry lists of new programs. Edwards’s bottom line: “In November, Americans will have to decide whether Kerry's big-spending promises are worse than Bush's big-spending record.”

But how to decide? We need to break out of the narrow mindset that trains all attention on the presidential candidates and their specific platforms and personal qualities. What matters far more is the balance of power. When one party is in charge of both Congress and the Presidency, the outcome is a spending binge, regardless of the party. Repeat after me: The pro-Kerry argument is not Kerry’s platform. The pro-Kerry argument is gridlock.

Monday, February 16, 2004

Picking Fights with Libertarians

I enjoy Mark Kleiman’s blog, despite often disagreeing with it. But Mark does have an odd penchant for picking fights with libertarians even when we agree with him. This happened a year ago, on the subject of laws that allow health insurance companies to break their contracts (see my responses here and here, both reaching into topics we do disagree on). It happened again last month, when he skewered Bush’s risible moonbase proposal (see my response here). And now it’s happened again, in a post on the FDA’s decision on the morning-after pill. “Once again,” he writes, “we can expect a deafening silence from the libertarians, whose sincerity about personal liberty I keep doing my level best not to doubt.”

Weird. It’s true that libertarians haven’t said much on this specific issue, though some have – read this and this and this. But on the other hand, libertarians generally argue that the FDA should be either emasculated or abolished entirely; here's a page articles from Cato, and an entire website run by the Independent Institute. I’m pretty sure Mark would not support eliminating the FDA, but the point is that doing so would make the morning-after pill issue moot; as long as abortion remained legal for even the first three days of pregnancy, the morning-after pill would be readily available. (As an aside, I should point out that there are many pro-life libertarians, though I’m pretty sure they are in the minority.)

I’m guessing the bigger issue is that Mark wants to know why libertarians aren’t opposing Bush. But more and more, they are. I, for one, have stated my opposition to George Bush repeatedly on this site. Radley Balko has been so critical of George Bush that he had to declare a week off from Bush-bashing – a pledge that he’s been unable to keep. Indeed, Bush-bashing is a favorite activity on most every libertarian site I visit. From Cato, here is a scathing indictment of his fiscal performance, here's another, and here's another from two years ago, before it got popular; here is an article criticizing the civil liberties record of John Ashcroft, and here is page of links on civil liberties under the Bush administration. If the question is why libertarians aren’t flocking to the Democrats, Mark should know the answer to that one: it’s because the Democrats are awful, too, on almost every front, including civil liberties. Lest we forget, Democrats voted for the civil-liberties-violating Patriot Act, Democrats voted for the political-speech-restricting Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act, Democrats voted for the nonpolitical-speech-restricting Child Online Protection Act, Democrats support hate speech laws, Democrats stand should-to-shoulder with Republican drug warriors. Even so, most libertarians I’ve spoken to are hoping a Democrat wins the next presidential election so that we can return to the glory days of gridlock.

UPDATE: In an update to his original post, Mark admits the silence has not been so deafening after all, posting a link to this post by libertarian Jacob Levy.